This is the story of an incredible fish.

Not long ago, it looked as if the magnificent Atlantic bluefin tuna would disappear forever from the Mediterranean.

The population was crashing in the face of huge overfishing, and the remaining stocks were being badly mismanaged as authorities ignored the warnings of experts and the industry continued to catch as many fish as it could.

Fishing communities watched as their livelihoods disappeared, and conservationists worried that the species might even become extinct.

The situation seemed hopeless – but today, things are different. The population is recovering, and a healthy future for the greatest of all our fish is a possibility. In fact, the scientific committee advising the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) is suggesting that fishing quotas for bluefin tuna stocks in the Mediterranean should be drastically increased.

WWF is very concerned. These same scientists warn that the proposed quotas will reduce the size of the bluefin population. So soon after rescuing this wonderful fish from extinction, it seems unwise to take any risks when we're so near recovery.

This could be one of the biggest conservation victories ever achieved in our region – but if we don't act carefully now, there's still a chance we could lose all the progress we've made.

© Frédéric Bassemayousse / WWF Mediterranean

We have to stay focused. Recovery and rebuilding was a huge challenge, and we must never make the same mistakes again. Sustainability is the only option for the future, and we’ve all got a role to play in that if we want the bluefin tuna to be here for our children and grandchildren to enjoy.

First, though, let’s meet the main character in our story…

Longlines, purse-seines, drift nets, harpoons… anything would do. Bluefin began to be hunted without limits around the world, with spotter planes and speedboats often used to find the shoals. As more fishers entered the market and more bluefin were caught, prices began to fall – so then fishing efforts redoubled. It was a disaster.

The western Atlantic fishery was the first to really suffer, and it happened fast. In 1960, around 1,000 tonnes were landed each year. By 1964, this had rocketed to 18,000 tonnes. Looking back, it's obvious that such big increases are totally unsustainable: by the end of the decade, landings had fallen 80% from their peak. It had taken just 10 years to destroy the regional stocks.

In the Mediterranean, it took longer: the population was larger and the market – at first – was smaller. But change was coming, and demand from Japan kept rising. Industrial-scale fishing for bluefin only really began in the early 1990s, but when it took off it was devastating for the stocks.

The biggest problem of all? It wasn't just the giants that the fishers were hunting. The introduction of bluefin tuna ranches in the Mediterranean – where smaller fish are fattened in captivity – opened a whole new market for younger tuna. Before they'd had a chance to spawn, huge numbers of juvenile tuna were captured alive at sea for transport to these ranches; meaning the breeding stock fell rapidly. No records were kept of the numbers caught.

1996: eastern Atlantic bluefin tuna stocks are placed on the IUCN red list, classified 'endangered'.

Astonishingly, there were no regional quotas at all until 1998. By this time, the crisis was clear: scientists and others could see what would happen if the exploitation of the bluefin stocks continued in the same way. A big reduction in the overall catch was needed: the population was down by 85% from historical levels. But expert views were seen as less important than the need for the fishing sector to make profits. Catch limits were set many times higher than the scientists advised, and the future was ignored.

It wasn't just that the quotas were too high. Monitoring and enforcement in the Mediterranean was very poor, and for several years the bluefin stocks suffered from high levels of Illegal, Unregulated and Unreported (IUU) fishing. Even 'legal' sales of bluefin added up to much more than the total allowable catch, and black market sales caused massive further damage.

Quotas were gradually reduced, but the pressure on the tuna wasn't: the main result of decreasing the quotas was to increase the amount of IUU fishing taking place.

By 2006, experts were predicting the extinction of bluefin tuna in the Mediterranean. It was time for a radical change.

Fishers, merchants, governments, scientists, conservationists, consumers: which of these groups wanted to see the bluefin go extinct in the Mediterranean?

The answer's obvious: none of them. But if that's true, which of these groups was in a position to save the bluefin?

The answer's obvious again: none of them. None of them working alone, that is – and here's where everything changed…

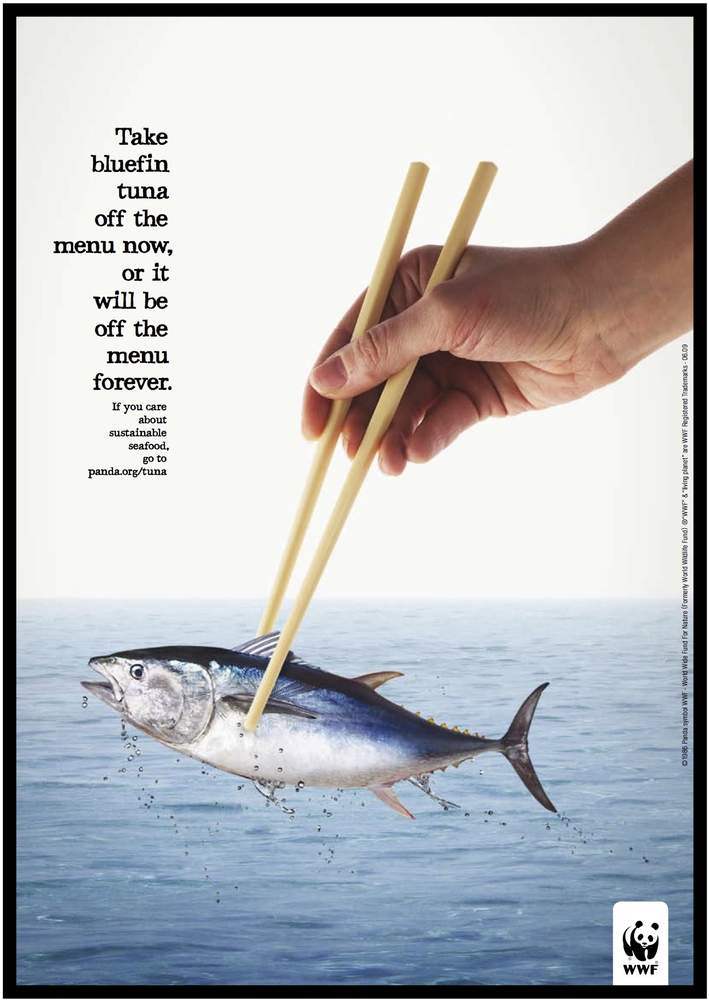

The campaign

We ran high profile publicity across international media

Ten years ago, WWF helped to launch a remarkable campaign. Several very different groups came together with a common purpose: to save the Atlantic bluefin tuna. By combining our efforts and sharing our resources, maybe we could persuade ICCAT to put proper conservation measures into place – but we all knew that this was our last chance.

ICCAT listened, and adopted a rigorous recovery plan. It set rules on total allowable catches, the length of the season, minimum size, bycatch management and recreational fisheries. It also brought in far more effective monitoring, control and reporting measures.

WWF's involvement focused on three particular areas: bringing parties together, science and advocacy.

We've always been good at bringing different groups together for dialogue: we're equally at ease on boats and in boardrooms, and if a government ministry wants to reach out to a village fishing cooperative then we often act as a go-between. With the Bluefin campaign, we've been front and centre throughout, and our eye-catching adverts took our message to the world.

There's something else at the heart of WWF's work: knowledge. The more you know about a problem, the more likely you are to solve it. And one of the difficulties with saving the Atlantic bluefin tuna? There were big gaps in our knowledge of the fish.

That's why we launched a unique research project in the Mediterranean. Over several years, WWF scientists worked with local fishermen to catch bluefin tuna, fit them with a special tracking tag, and release them. Over the following months the tag would record data, allowing us to track the movements of the fish.

One of the Bluefin tags – with a €300 reward for returning it!

© Frédéric Bassemayousse

/ WWF Mediterranean

Over time, we built a new picture of the migration and breeding habits of the Atlantic bluefin tuna population. The data was invaluable in developing a science-based management and recovery programme.

You can join the team aboard the tagging boat – and see some of these amazing ocean giants up close – in this short film we made about the tuna trail…

What happens next?

The situation for bluefin tuna in the Mediterranean today is potentially good – the stock is recovering, but

it's not there yet, and we're at a crucial point in the process.

Some policymakers look at the success of the recovery plan and understand the importance of continuing it. Others look at it and believe the work is already done. But if we abandon the recovery plan and raise quotas too quickly, as is proposed, we could lose all the progress we've made.

Today, the stock is well managed and there are reliable monitoring and control systems in place, but we need a strong and sustainable stock management plan for the future – and finding a consensus is a complex operation. Scientific advice on quotas has to be balanced with political pressure from fishing nations who want to increase their catch, and at the moment we're very concerned by the risk that ICCATT will set limits that are too high for a sustainable future. Experts still aren't sure we know enough about the rate at which the stocks will reproduce to guarantee that they're secure, and it seems obvious that any proposals that will actually reduce the number of bluefin tuna in the water are bad proposals.

WWF is talking to everybody involved, promoting dialogue between scientists, politicians, policymakers, retailers and fishers: it's essential to make sensible decisions that work for everybody, and those decisions have to promote healthy stocks now and in the future. Short-term profit can't be more important than long-term sustainability.

Markets make a big difference, and this is another area we're working on. WWF wants to see an increased focus on small-scale bluefin tuna fisheries, which can help regenerate traditional coastal communities around the Mediterranean. However, small-scale doesn't necessarily mean low-impact, so it's extremely important that these fisheries, too, are carefully monitored and managed.

We're so nearly there. There's been an enormous amount of excellent work done to save the bluefin tuna, and if we can keep up our efforts for a little while longer then there's every chance that we'll be able to leave a healthy population of this wonderful fish as a legacy for our children and grandchildren.

We're going to keep fighting for bluefin tuna – and it's a fight we intend to win once and for all.

© Wild Wonders of Europe / Zankl / WWF

The power of the consumer

So what about actually eating bluefin tuna? The population is on the way to recovery, but it's not there yet – so WWF recommends consuming it in moderation. Origin matters, too: we're asking consumers to get informed on where the fish comes from, and to choose wild-caught tuna rather than farmed tuna wherever possible. We also call on businesses to join the fight against illegal fishing, and make sure they're only buying and selling tuna from legal sources.

If we can save the bluefin tuna, there's no reason why we can't also restore the rest of the Mediterranean's fish stocks, regenerating one of the world's most important seas and leaving a priceless resource for future generations.

The good news is it's not complicated: consumers have more power than ever before, and by buying sustainable seafood in the shops we're directly supporting sustainable oceans.

But we need to know what we're buying. That's why WWF have produced a multilingual Sustainable Seafood Guide. This online resource surveys a wide range of species available in 12 European countries and rates them with a traffic light system, running from blue for ‘certified’ through green for ‘give it a try’ and orange for ‘caution’ to red for ‘avoid’.

You can find links to the Sustainable Seafood Guide for each country by clicking here.